This is a guest blog-post by Professor C.E. McGee, who was the recipient of the Colin Baldwin Fellowship for 2017 for his work on the Records of Early English Drama (REED).

The Emerging Picture of Performances in the Clifford Household

Thanks to a grant from the Malone Society, I had the opportunity to spend several days working on Clifford family records at Chatsworth House for the REED North-East project. The focus of this research was the entertainment of King James I by Sir Francis Clifford, Earl of Cumberland, during the king’s progress from Scotland in 1617. For our knowledge of these entertainments, we are deeply indebted to the late R. T. Spence, who published a richly detailed narrative of the events in ‘A Royal Progress in the North: James I at Carlisle Castle and the Feast of Brougham, August 1617’, Northern History 27 (1991), 41-89. He drew heavily on the stewards’ accounts, noting, closely paraphrasing, or quoting from entries in these accounts. My aim was to locate the evidence of performance Spence integrated into his article, supplement it if more could be found, and supply the specific references that he did not.

Francis Clifford, fourth Earl of Cumberland

Skipton Castle, North Yorkshire

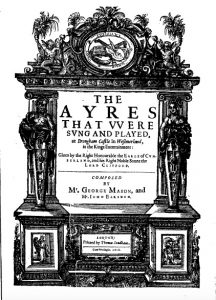

Doing this research confirmed my impression of how remarkable the Cliffords’ entertainment of King James was. Sir Francis took special care with the lavish celebrations at Brougham Castle in Cumbria. For this occasion, he hired the poet, composer, lutenist, and writer of court masques, Thomas Campion, who ‘Composed the whole matter, Songs etc.’ Campion received the remarkable reward of £66 13s. 4d. ‘for his paines therein, Coming downe to prepare, order it, and see all Acted, & for his Charges to and fro’ (Spence, 59). While Campion played a key role, Clifford also took advantage of the creativity and talent of his family and household. His son Henry (1591-1643), styled Lord Clifford and later 5th Earl of Cumberland, was responsible for inventing the device of the show. For its performance, the earl enlisted musicians in the service of his son-in-law Sir Gervais Clifton, employed John Johnson the headmaster of St. Peter’s School in York to sing, brought in a musician from Hull just in case he was needed, and entrusted two musicians who were currently, or had recently been, in his household – John Earsden and George Mason – to create the settings and to perform. Their work, The Ayres that were Sung and Played, at Brougham Castle (London, 1618), offers the only glimpse we have of the content of the three separate shows on successive evenings during the king’s visit.

The Ayres that were Sung and Played, at Brougham Castle (London, 1618; STC 17601)

Image from Early English Books Online

Campion may have brought some of the sophistication of court music to the Clifford estate, but the musicians there demonstrated that they were up to the performance of it. That the Clifford family, household, extended family, and nearby associates in Yorkshire could invent the device, compose and play the music, sing, dance, and enact the script testified to the family’s nobility, accomplishments, and prestige. For Campion, the Brougham Castle entertainment confirmed his high praise for Clifford, the patron, ‘Whose House the Muses pallace I haue knowne’ (‘Dedication’, Two Books of Ayres [1613]).

My effort to recover and document the evidence of performances at Carlisle and Brougham Castles was successful, but not entirely so. The Westmorland account of John Taylor, noted by Spence as ‘Unlisted’, is still unlisted and could not be found during my time at Chatsworth House. Unfortunately, this manuscript is a key one: it includes the payment of £66 to Campion and documents how Sir Francis financed the entertainment, for Taylor was his agent in London and the earl raised much of the funding there. The account of the king’s visit that Spence provides also suggests that Taylor’s account is particularly valuable because it covered the period when the celebrations actually occurred. All the other stewards’ accounts cease about a week before the big event and begin again about a week afterwards. Presumably all household staff were in attendance at Brougham where they were needed.

The east side of Brougham Castle, Cumbria

Photograph by Paul Farmer

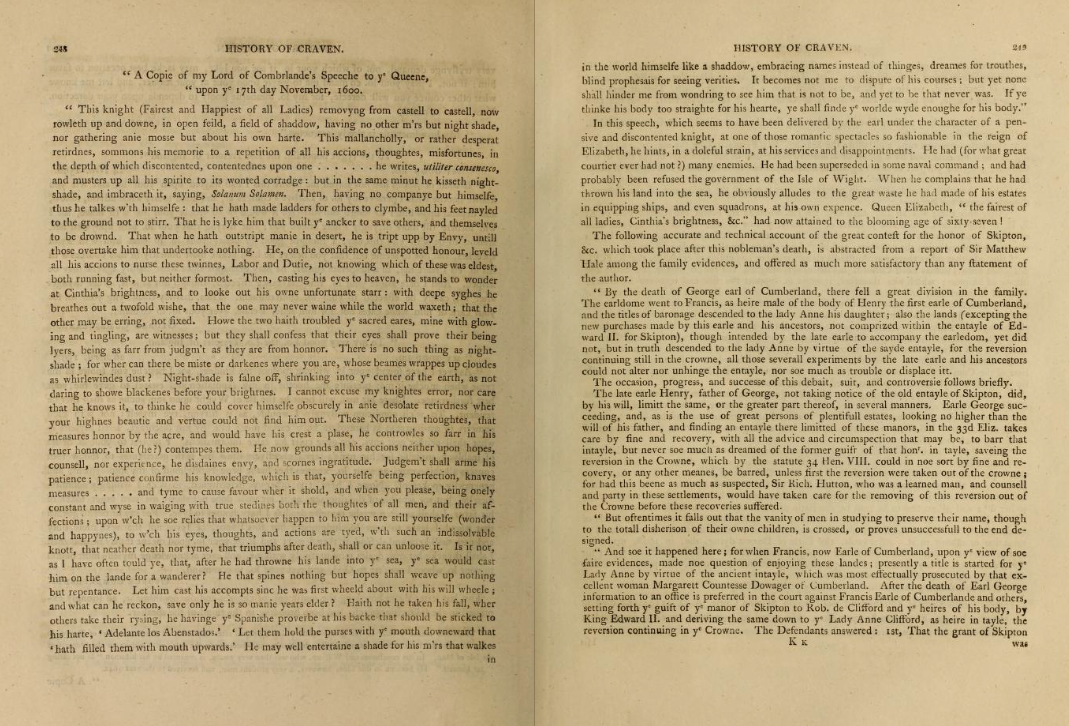

The search for this account book led to a serendipitous discovery however. In going through boxes of miscellaneous papers that the archivist produced, I found the original manuscript of the third Earl of Cumberland’s speech at the tiltyard on Accession Day 1600. We have had T.D. Whitaker’s edition in The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven since 1805 and a reference for that document – Bolton Abbey MSS. Sundry Documents #54 – since at least 1987, but efforts to find it had failed, because the specific document is numbered, but the box in which it is found is completely unmarked. This speech and that of Lord Compton on the same occasion illustrate how tiltyard devices could combine routine praise of the Queen and protestations of devoted service with personal complaints and petitions. The Earl of Cumberland appears in the lists as a ‘Melancholy Knight’, lamenting his financial losses at the hands of others. Lord Compton appeals to the Queen to dissolve ‘a marble stone’, that is, the heart of his father-in-law, Alderman Sir John Spencer, who had disinherited his daughter because he disapproved of her marriage.

T.D. Whitaker’s edition of the third Earl of Cumberland’s Accession Day speech in

The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven (1805) (click on the image to read the text)

Both the failure to find John Taylor’s Westmorland account for 1617 and the surprising discovery of Cumberland’s speech at the tilt suggest that the picture of performance activity rewarded by the Cliffords is still emerging. Records of dramatic activity for the family have been emerging for many years. Whitaker included payments to seven companies of travelling players in his History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven (1805). The number of records of such performances more than quadrupled when Lawrence Stone revisited the Bolton Abbey manuscripts at Chatsworth. Searching the financial records of the Francis Earl of Cumberland and Henry Lord Clifford from 1607 to 1639, he discovered the evidence of thirty-one rewards to troupes of players. His findings, published by the Malone Society in Collections V (1959 [1960]), demonstrated the importance of household records for knowledge of actors travelling in the north of England.

John Wasson and Barbara Palmer, the late REED editors of the Derbyshire and Yorkshire West Riding, took Stone’s work further. He had thought that the players probably received food and lodging because some performances occurred after supper. This idea remained conjectural because, he noted, “there are no kitchen accounts with which to check this point” (19). Wasson and Palmer, however, found the ‘Pantry Accounts’ for the Clifford household; indeed, they are extant for the same eight-month period in 1612 that Stone focused on when he illustrated the variety and frequency of visiting performers. For each day, the Pantry Accounts list ordinary members of the household on the left page, extraordinary members on the facing page. Individual entries contain only the information needed for accounting purposes: who dined, how many, and at what meal. As a result, to Stone’s record of a payment in this Household Accounts –

1611/12 March 14, at Londesborough

Item giuen this day in rewarde to the Queenes Players by my Lord’s Comandment. whoe Played one Play this day after dinner Fourtie Shillinges xls (21) –

we can add this information from the Pantry Accounts:

14 March

Twelve players diner (Bolton Abbey MS 59, f. 34)

In this instance the Pantry Account tells us the size of the Queen’s men on this occasion. Other Pantry Account entries provide evidence of troupes of players unrecorded in the Household Accounts; for example, just a little later in March 1612, a company of 14 players had three meals in the household over a two-day stay. Besides recovering the Pantry Accounts, Palmer and Wasson extended their search in accordance with REED’s parameters. As a result, we have scores of payments to musicians from as early as 1510 and eighteen more records of travelling companies of actors between 1590 and 1607, the starting point of Lawrence Stone’s work.

During my time at Chatsworth House last summer, I focused on the accounts books from 1616 to 1619, the period before and after the Earl of Cumberland’s entertainment for King James I. A close reading of these books produced no new information about the festivities for the king or about visits of companies of actors to Clifford estates. I was surprised to find, however, in sections of the account books devoted to ‘Riding Charges’, ‘Carriage Costs’, and ‘Apparell’ a significant cache of payments for town waits, musicians, instrument makers, music books, and musical instruments along with expenses for their care, repair, transport, and supplies. These records of performance activity at the Cliffords’ estates in the north of England represent only part of the emerging picture of their patronage. We have to supplement those records both their rewards (almost daily rewards) to musicians when they travelled to and from London and their expenditures to attend masques at court and plays in London’s public theatres. The ‘complete’ picture of the Clifford household records of performance promises to be rich and complex.